After banning sugar exports, the Centre has taken the next step towards augmenting domestic availability – restricting diversion of the sweetener for ethanol production.

On December 7, the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution directed all mills and distilleries not to use sugarcane juice/syrup for making any ethanol “with immediate effect”.

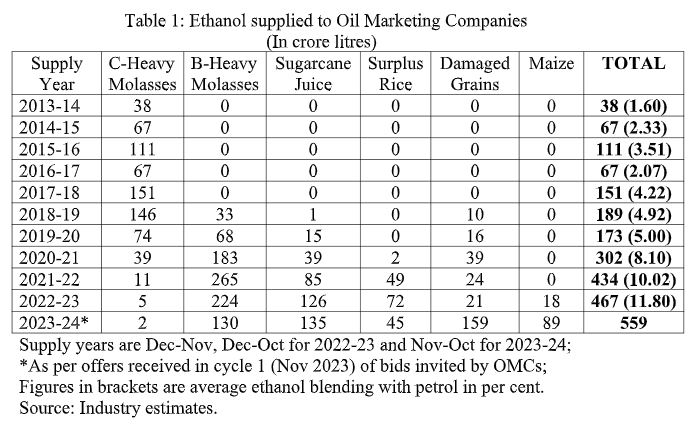

Ethanol is 99.9% pure alcohol that can be blended with petrol. The ethanol blended petrol (EBP) programme has been a significant accomplishment of the Narendra Modi government. The all-India average blending of ethanol with petrol has risen from 1.6% in 2013-14 to 11.8% in 2022-23.

Alternative feedstocks

Key to this has been feedstock diversification.

Ethanol – or even 94% pure industrial-grade rectified spirit and 96% extra neutral alcohol for potable liquor – is normally made from so-called C-heavy molasses. Mills typically crush cane with 13.5-14% total fermentable sugars (TFS). Around 11.5% of it can be recovered from the juice as sugar. The uncrystallised, non-recoverable 2-2.5% TFS goes into C-heavy molasses. Every tonne of this liquid, containing 40-45% sugar, gives 220-225 litres of ethanol on fermentation and distillation.

But mills, instead of recovering 11.5% sugar, can extract just 9.5-10% and divert the balance 1.5-2% TFS to an earlier ‘B-heavy’ stage molasses. This molasses, having 50%-plus sugar, yields 290-320 litres of ethanol per tonne. A third option is not to produce any sugar and ferment the entire 13.5-14% TFS into ethanol. From one tonne of cane, 80-81 litres of ethanol can thus be obtained, as against 20-21 litres and 10-11 litres through the B-heavy and C-heavy molasses routes respectively.

The increase in India’s ethanol production happened largely after 2017-18, when mills started making it from B-heavy molasses and concentrated sugarcane juice/syrup (Table 1). In addition, new substrates – surplus rice from the Food Corporation of India’s (FCI) stocks, broken/damaged foodgrains, and maize – were used. Grains contain starch, which has to be converted into sucrose and simpler sugars (glucose and fructose) before their fermentation by yeast. The longer process notwithstanding – molasses already have fermentable sugars – ethanol yields from grain are higher, at 380-480 litres per tonne.

The real fillip to EBP programme came with the Modi government paying mills more for ethanol produced from feedstocks other than C-heavy molasses. For 2022-23, the ex-distillery price of ethanol payable by state-owned oil marketing companies (OMS) was fixed at Rs 49.41 per litre if made from C-heavy molasses, but at Rs 60.73, Rs 65.61, Rs 58.50, Rs 55.54 and Rs 56.35 if from B-heavy molasses, sugarcane juice/syrup, surplus FCI rice, broken/damaged grain and maize respectively. In previous supply years (December-November) till 2017-18, the OMCs paid a uniform price for ethanol irrespective of feedstock.

Tarun Sawhney, vice chairman and managing director of Triveni Engineering & Industries Ltd (TEIL), credits the EBP programme’s success to the differential pricing policy.

TIEL’s distilleries in Uttar Pradesh run on multiple feedstocks – B-heavy molasses during the cane crushing season (November-April) and grain in the off-season (May-October). The latter mainly comprised FCI rice, the supply of which was stopped from July 2023 on concerns over depleting stocks. The company, then, switched to damaged/broken rice and maize sourced from the open market at higher prices. The Centre, on its part, also raised the procurement price of ethanol produced from damaged grain and maize to Rs 64 and Rs 66.07 per litre respectively in August.

“The government’s ethanol policy has been very supportive, especially with regard to pricing and use of alternative feedstocks. The EBP programme no longer relies on a single feedstock or crop. Earlier, 100% of ethanol was from sugarcane-based feedstocks (it fell to 76% in 2022-23). I see that share dropping below 50%, and correspondingly going up for grain, in the coming year,” said Sawhney.

Not so sweet

The December 7 directive is, nevertheless, a setback for the industry – more so for companies such as Balrampur Chini Mills, Shree Renuka Sugars, Ugar Sugar Works and Nirani Sugars, which have set up capacities to produce ethanol directly from cane juice/syrup.

The OMCs had floated a tender for the supply of around 825 crore litres of ethanol for 2023-24, translating into a 15% blending target. In the first cycle of bids early last month, they received offers for some 559 crore litres, out of which ethanol produced from sugarcane juice/syrup accounted for 135 crore litres. The December 7 order could impact the bulk of the latter supplies, leading to stranded capacities.

The Centre has, for now, stated that the supply of ethanol from B-heavy molasses against “existing offers received by OMCs…will continue”. However, it is yet to announce prices for ethanol from various feedstocks payable to mills in 2023-24. This is despite the ethanol supply year being moved from December-November to November-October now, closer to the sugar year from October when mills commence crushing.

Sugar supply concerns

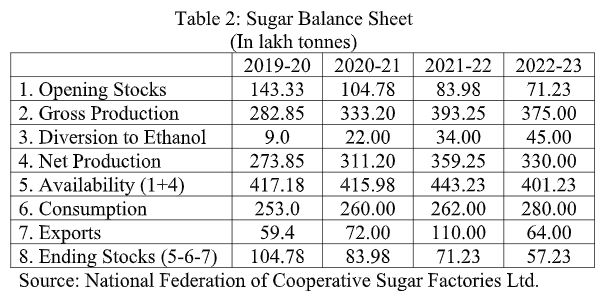

The reason for the Centre’s seemingly going slow on ethanol blending is simple. The 2022-23 sugar year ended with stocks of just over 57 lakh tonnes (lt), the lowest since the 39.4 lt of 2016-17 and way below the record 143.3 lt of 2018-19 (Table 2).

Six-year-low opening stocks apart, there is uncertainty over production for the current 2023-24 year itself. The National Federation of Cooperative Sugar Factories has estimated this year’s output at 291.50 lt, down from 330.9 lt and 359.25 lt in 2022-23 and 2021-22 respectively. Maharashtra and Karnataka are expected to record particularly sharp declines, on the back of subpar rains and low reservoir water levels in their major cane-growing areas.

The December 7 order is likely to result in roughly 15 lt of additional sugar, which would have otherwise gone for ethanol production through the cane juice/syrup route. This extra sugar coming into the market will, more than boosting physical availability, help douse any bullish price sentiment.

The latest decision, taken together with the ban on sugar shipments since May 2023, makes one thing clear. When it comes to domestic supply over exports, consumers over producers and food over fuel, governments privilege the former. This government even more so.

Harish DamodaranThe writer is the National Rural Affairs and Agriculture Editor for Th… read more

Harish DamodaranThe writer is the National Rural Affairs and Agriculture Editor for Th… read more